The Washington Post [3/1/04]

50 Years Later, Nuclear Blast Felt on Bikini Atoll

50 Years Later, Nuclear Blast Felt on Bikini Atoll

Via Reuters

Monday, March 1, 2004; 9:30 AM

By Ben Gruber

BIKINI ATOLL, Marshall Islands (Reuters) - At first glance, it looks like a tropical paradise: an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, where palm trees encircling a pristine blue-green lagoon sway in the breeze.

But to the native islanders, Bikini Atoll is more like an exhausted, scorched wasteland, where they eke out an existence in a place that today is forgotten by much of the world. But on March 1, 1954, it became ground zero during the Cold War.

A half century ago on Monday, the United States conducted its largest nuclear test. Code-named Bravo, a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb detonated on Bikini Atoll, producing an intense fireball followed by a 20-mile-high mushroom cloud.

The hurricane-force winds generated by the blast stripped the branches and coconuts from Bikini's remaining trees. A small fleet of ships, including the USS Saratoga and the Nagato, Japanese Admiral Yamamoto's flagship, were engulfed in the nuclear explosion and plunged to the bottom of the lagoon.

Radioactive fallout spread quickly, drifting toward Rongelap, an inhabited island nearby. Survivors remember the event vividly.

"It was the first time I saw the sun rise in the West," recalls Lemyo Enob, age 14 at the time. "At first, I did not know what it was, but then I understand it was a big bomb."

The 'sun' that day was a thousand times more powerful than the blast at Hiroshima, the Japanese city where the first atomic bomb was dropped and prompted the end of World War II.

He also remembers the effects of the fallout from the bomb: "Something like powder fell on us, Some of the people got nausea, some had diarrhea and they became red."

Although the U.S. nuclear testing campaign at the islands ended in 1958, its legacy became more evident in the years that followed, with the slow emergence of long-term health effects of the islanders' radiation exposure.

Jack Niedenthal, as the trust liaison for the people of Bikini, tries to represent their interests to governments thousands of miles away.

SUFFERING ALL AROUND

"There are a lot of cancers out in the Marshall islands," Niedenthal says. "I can just go down the list of my wife's family. ... My wife's mother died of cancer of the uterus, my wife's uncle died of thyroid cancer." Nearly every islander can scan his family and see the same suffering, he said.

With only a few doctors, the hospital on Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, is repeatedly overwhelmed. Hundreds of people line up to wait for appointments with the understaffed medical team.

Niedenthal says the long-term effect of radiation is only one of the health hurdles the Marshallese face. The introduction of processed foods to people who had once subsisted solely on fish and fruits has created unwanted medical conditions: diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity.

And for the Bikinians, life has never been the same since the U.S. military moved them from their homes in 1946, when the Cold War started. The atoll became a test site for what would turn out to be a total of 23 atomic and hydrogen bomb tests to gauge the effects the blasts would have on warships and to maintain America's nuclear superiority.

But it would prove more devastating to the people.

The Bikinians were moved to Rongerik Atoll, which had a much smaller food supply, and within weeks they faced starvation. They eventually asked to be returned to their native land, but their homes were now located on radioactive wasteland.

Over the next 20 years, the Bikinians were moved several times. In 1967 some 150 people were returned to Bikini, only to be evacuated again when it was discovered that radioactive Cesium 137 had contaminated the food chain.

A SCATTERED PEOPLE

Today Bikinians remain scattered throughout the Marshall Islands. On Ejit Island, bare-footed children play marbles outside shanty homes as women wash plastic dishes in aluminum containers. The children swim in the lagoon and eat indigenous fruit such as pandanas and coconuts after returning from school where they learn English from foreign volunteers.

There is little economic activity to bring in foreign capital. Ironically, the testing left a treasure trove for dive enthusiasts who explore the sunken U.S. and Japanese aircraft carriers, warships and submarines off Bikini Atoll.

While fish from the lagoon are considered safe for consumption, tourists are not allowed to eat local vegetation, still considered toxic because of radioactive elements.

"People always ask me if I glow in the dark," joked head dive master Tim Williams.

However, tourism earnings are not enough to sustain the islanders. More than half of the country's income is derived from U.S assistance, and most Marshallese live on less than a dollar a day, said one Marshallese official.

The people of Bikini Atoll want the U.S government to fulfill a promise it made more than half a century ago -- to restore their homeland to the way it was prior to nuclear testing. But a Bush administration official in February could not confirm that U.S. promise.

Niedenthal, who has visited Washington with Bikinian leaders, says the fight for reparations has not been easy.

Under agreements between the United States and the Marshall Islands, a Nuclear Claims Tribunal was established to assess and award damages to victims of the nuclear tests. In 1999, the tribunal awarded more than $500 million to the people of Bikini and to complete its cleanup.

But the tribunal has never had the cash to fully compensate the Marshallese for the damage done, although a Bush administration official said U.S. assistance to the Marshall Islands is "one of the largest aid packages per capita in the world."

Officials in the Marshallese government say it would take $1.5 to $2.5 billion to complete the cleanup and to compensate the victims of the tests -- a fraction of the billions to be spent rebuilding Iraq.

Tomaki Juda, a Marshallese senator, notes the U.S. expenditures to help rebuild the infrastructure destroyed by the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. "Why won't they do the same for us?" he asks.

This Bikini Atoll website is sponsored by: To purchase or rent Microwave Films and DVDs MICROWAVE FILMS

|

|

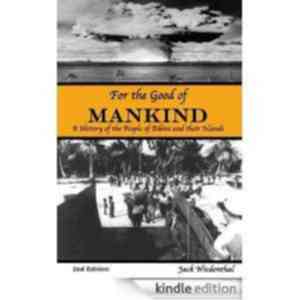

The historical information within this site, while constantly updated, is drawn largely from the book, FOR THE GOOD OF MANKIND: A History of the People of Bikini and their Islands, Second Edition, published in September of 2001 by Jack Niedenthal. This book tells the story of the people of Bikini from their point of view via interviews, and the author's more than two decades of firsthand experiences with elder Bikinians. Copies can be purchased from this direct ordering link at Amazon.com, or you can also buy and download the Kindle edition. |